Among evangelical Christians there is a widespread, even dogmatic belief that every Christian has a duty to evangelize unbelievers, that is, to explicitly share the Gospel with them in order to persuade them to come to belief. If you’re an evangelical Christian reading this, you’re probably thinking, “Well, yes, of course Christians have a duty to do that.” But is this really true? Are there any biblical grounds for thinking that every Christian has a moral obligation to evangelize? I don’t think so. In fact, I don’t think there is a shred of biblical evidence for this.

Now let me explain my claim a bit by clarifying what I am not saying. First, I am not saying that Christians do not have a biblical duty to be prepared to intelligently explain the Gospel when asked. This much is clear in the apostle Peter’s directive to “Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect” (1 Peter 3:15). Clearly, Peter is saying that all Christians have a duty to be ready to explain the Gospel and even provide some apologetic grounding for their beliefs. But notice that this is an injunction to respond to those who inquire, not a command to actively initiate such conversations in order to persuade others.

Secondly, I am not suggesting that it is unbiblical or morally wrong for individual Christians to do evangelism. In fact, it is overwhelmingly clear in Scripture that well-planned initiatives to persuade people of the Gospel are appropriate and wise in various circumstances. This is obvious from Jesus’ sending out his disciples two-by-two to spread the good news (Luke 9:1-6 and Luke 10:1-11) and numerous instances in the book of Acts where Christian leaders evangelized (Acts 5:42; Acts 8:4-13, etc.). However, note that these are specific initiatives that do not imply a universal duty to evangelize, though they might support the notion that Christian church leaders have a duty to  evangelize. In fact, the apostle Paul confesses that “when I preach the gospel, I cannot boast, since I am compelled to preach. Woe to me if I do not preach the gospel!” (1 Cor. 9:16). But in that passage, Paul is speaking for himself and perhaps, by extension, other apostles, as the context of that passage is Paul’s defense of his rights as an apostle.

evangelize. In fact, the apostle Paul confesses that “when I preach the gospel, I cannot boast, since I am compelled to preach. Woe to me if I do not preach the gospel!” (1 Cor. 9:16). But in that passage, Paul is speaking for himself and perhaps, by extension, other apostles, as the context of that passage is Paul’s defense of his rights as an apostle.

Thirdly, I am not suggesting that the Church, as a body of believers, does not have a duty to evangelize unbelievers. Clearly, evangelism is an obligation of the Church. For as Paul says elsewhere, “How . . . can they call on the one they have not believed in? And how can they believe in the one of whom they have not heard? And how can they hear without someone preaching to them? And how can anyone preach unless they are sent?” (Romans 10:14-15). Moreover, there is the Great Commission which is given by Jesus himself: “Go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age” (Matt. 28:19-20). But while these passages imply that the Church should spread the Gospel, neither of these passages imply that each individual Christian has a duty to bear this burden. And to suggest that the former implies the latter is to commit the logical fallacy of division (illicitly reasoning from an attribute of a whole to that of its parts).

So by rejecting the notion of a universal Christian duty to evangelize I am not suggesting that evangelism is wrong, that Christians need not be prepared to defend the Gospel, nor even that the Christian church has no duty to evangelize. I am suggesting that evangelism is a crucial function of the Church that should be intentionally carried out by those who are especially well-prepared—and I would say specially gifted—to perform. I would compare the gift of evangelism to such spiritual gifts as prophecy, teaching, and church leadership (1 Cor. 12:8-10 and Rom. 12:6-8). Such are crucial functions within the church, but it would be absurd to suggest that every Christian has a duty to prophesy, teach, and be a church leader. No, as Paul says, not all members of the body of Christ have the same function (Rom. 12:4). Similarly, although evangelism is an important task of the church, not everyone is called or properly gifted to perform that task. (For more on this idea, check out Bryan Stone’s book Evangelism After Christendom.)

Yet the myth of a universal Christian duty to evangelize is extremely popular among evangelicals these days. Given the way that some Christian leaders emphasize and even guilt trip congregations about it, it is tempting to classify this as a modern pharisaism, a way in which Christian leaders have bound the consciences of Christians, effectively adding to the law. I am not exaggerating when I say that I’ve heard more sermons proclaiming a supposed universal Christian duty of evangelism than I have heard proclaim any of the Ten Commandments as moral duties. What is wrong with this picture?

So where did this idea come from? If there are no biblical grounds for an individual mandate to evangelize, then why is this misconception so popular among evangelicals? In short, I believe it is a consequence of Western, particularly American capitalistic thinking as applied to Christian public life. In other words, I think the idea resulted more from market and sales thinking than from Scripture. This is my best guess anyway. (For more on the connection between evangelism and marketing, see the Kenneson and Street book Selling out the Church.)

Speaking of history, consider a final point that should prompt doubt in the minds of even the most stalwart defenders of a universal duty to evangelize. So far as I can tell, none of the greatest Christian theologians and spiritual leaders ever taught this doctrine. I challenge you to locate it in any of the early church fathers (St. Ignatius, Clement of Alexandria, Athanasius, John Chrysostom, Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, John Cassian, Augustine), the great medieval theologians (Anselm, Bernard of Clairvaux, St. Francis of Assisi, St. Dominic, Thomas Aquinas), the Reformation era theologians (Martin Luther, John Calvin, John Knox, Ulrich Zwingli, Teresa of Avila), Revivalist theologians (John Wesley, Charles Wesley, Jonathan Edwards, and George Whitefield) and the greatest 20th century theological minds (Karl Barth, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and C.S. Lewis). That’s 25 of the greatest Christian minds—and certainly inclusive of the greatest Christian theological minds—in world history. Yet apparently none of them believed that there is a universal Christian duty to do evangelism. Now if that teaching was a biblical one, I think its safe to say that most, if not all, of these folks would have picked up on that. Right? So what gives?

If you’re a conservative evangelical, you’re probably bothered by what you’ve just read. But my plea to you is to honestly reflect on whether your view is actually biblical. I would also urge you to consider the force of the fact that there is no evidence that any of the greatest theological minds in history agree with you. That fact alone should give any Christian serious pause.

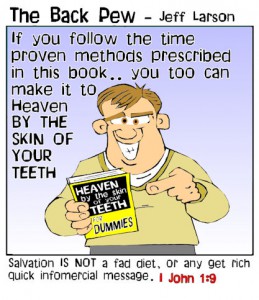

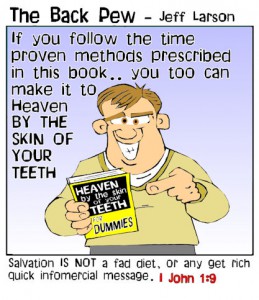

Now, finally, why does this matter? Even if we did get this one wrong, you may ask, isn’t it better to err in the direction of zeal than complacency when it comes to evangelizing others? I don’t think so, and here are three reasons why. First, it is wrong and harmful to bind people’s consciences. Legalism is deadly for Christian faith and spiritual formation. Secondly, the myth of a universal duty to evangelize has undoubtedly compromised the power of the Church’s witness, since this myth has had the effect of prompting incompetent evangelizing which poorly represents the Gospel. Thirdly, this myth has created a tragic association of Christianity with cheap marketing, thus making conservative Christianity synonymous with insincere, means-to-an-end salesmanship and kitschy sales techniques. (I’m sure we can all think of many cringe-worthy examples we have personally witnessed.) This, of course, is the most ironic distortion of Christianity, representing the Gospel as something precisely opposite what it is.

So, in summation, the answer to the question “Is evangelism biblical?” is, of course, yes. It is clearly biblical that the church has a duty to spread the Gospel message. But what is not biblical is the notion that there is an individual mandate for Christians to evangelize other people. For those who feel so led or, better, have the gift of evangelism, it is perfectly appropriate for them to do so, given the right circumstances. But the duty for all Christians is to be prepared to answer those who ask them about the Gospel and, most importantly, to live virtuous lives, displaying the fruit of the Spirit (“love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, gentleness, goodness, faithfulness, and self-control”—Gal. 5:22-23). Now these are universal mandates that are biblical. And if we Christians were all more serious in pursuing them, I bet the Church would be far more effective in fulfilling the Great Commission.